I’d prepped most of this for my “Stories I’ve tried to write week” and then a plot idea emerged. I was discussing things with Andrew, over on a Shewstone planning list, and while we were discussing something else entirely he gave me the key to moving this post to a workable series of scenarios for Ars Magica. It might also work for Magonomia, but I’d need to think about it rather harder. I’m already working on a shadow-city for Ars Magica, and a Shadow London seems a bite too many.

There’s a lengthy poem by James Thomson called “The City of Dreadful Night” where he lays the nihilism on so thick that people at the time of publication were impressed by how unremittingly bleak it is. He never lets a crack of hope get in, other than the contemplation that at least death is the end of all this pain and bother. This may, of course, seem a bit obvious and played out to modern readers, because agnostic materialism is popular now, but at the time he was considered a bizarre bird. He didn’t go in for Decadence, which was the popular line for nihilists at the time. Later in the year I’ll share his version of Swinburne’s three ladies, and you’ll see that his approach is not opium and debauchery in the face of inevitable death. He’d just like to pick the death that is most pleasant, and ask her to get on with it. His angels of insomnia are awesome too, and they’ll also be by later.

My initial plan was to use a section of the poem each post for “Every Day In May”, but I don’t want to snow my distribution channels with nihilism. My current plan is to take this poem and break it into four sections, describing the plot hooks in each. Unlike other long poems, which I’ve played and then commented on, for this one it’ll be comments, then the poem as demonstration.

The City of Dreadful Night is a regio that seeks out sleepers and takes their dreaming selves. It is a nightmare, yes, but worse, it also seems to claim people after death. Having dreamt of the City, you are more likely to dream again of the City. The City is filled with vignettes of hopelessness. I thought it was useless as a play setting, because the vignettes are too static.

Then I remembered the Hounds of God. In Ars Magica there’s an order of werewolves who annually storm Hell and break the place up, stealing the fertility of the Earth back from Satan. Why not just let the players loose on the vignettes, to break the place up and wreck it for whatever is making this place so terrible?

Certainly, this is a betrayal of Thompson’s intention: you are not, as reader meant, to imagine yourself tracing a sleeper back to the earth and giving him a dose of Creo Mentem spells. You are not meant to imagine a magician putting a net under the bridge over the River of Suicides It might not be entirely in the spirit of the thing to fling Pila of Fire at the infernal toll collectors at Hell’s Gate. Then again, Thomson is dead and expected very little of posterity, so I feel that by disappointing him, I’d give him a grim satisfaction.

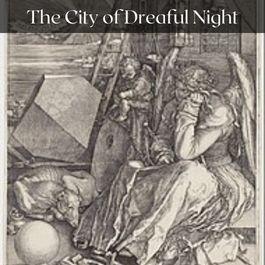

To skip to the end, to give some structure, there is one creature that may act as a lynchpin for the regio, either a saviour for the people, or their oppressor. It is mentioned in the last chapter, so I wanted to give her now, as context. A statue of the Goddess of Melecolia lies outside the city, on the bare northern plateau, so that it is visible much of the time. The narrator seems to find some peace in knowing that others are suffering much as he is. The goddess is based on a print by Durer, Melencholia I. Yes, the spelling is irregular – there’s some debate as to if he meant Melancholia or something more obscure. There’s a plethora of discussion of this engraving and I’d suggest you look it up. Much like Durer’s figure, the goddess of the city of night is surrounded by magical and geometrical instruments. She may be a spirit of alchemy, and she has the first magic square seen in European print. Also, what the “I” stands for is unclear: she may be a guide to the first stage of alchemy (black stone, disintegration) or it may be a reference to Durer, or there may be three lost prints for the other Temperaments based on bodily humours. A very high quality scan is available from Wikipedia which describes the objects in the image.

The City of Dreadful Night was recorded for Librivox by MoonLylith. Thanks to the reader and their production team.

The proem describes why he wrote the book. If you say “Hey, everything is terrible and pointless.” you need to explain why to put your pen to paper. In Ars Magica terms, it lets you get back a Confidence point, because it gives you the solace of knowing you are not alone. It also seems likely that if you have some of the positive emotional or spiritual Virtues, you simply cannot read this text. You need to be a melancholy sort. My question is, if you are a melancholy sort and read this book in the real world, does it make the regio come for you? Is this, in essence, a seed or doorway for the Infernal?

PROEM

Lo, thus, as prostrate, “In the dust I write

My heart’s deep languor and my soul’s sad tears.”

Yet why evoke the spectres of black night

To blot the sunshine of exultant years?

Why disinter dead faith from mouldering hidden?

Why break the seals of mute despair unbidden,

And wail life’s discords into careless ears?

Because a cold rage seizes one at whiles

To show the bitter old and wrinkled truth

Stripped naked of all vesture that beguiles,

False dreams, false hopes, false masks and modes of youth;

Because it gives some sense of power and passion

In helpless innocence to try to fashion

Our woe in living words howe’er uncouth.

Surely I write not for the hopeful young,

Or those who deem their happiness of worth,

Or such as pasture and grow fat among

The shows of life and feel nor doubt nor dearth,

Or pious spirits with a God above them

To sanctify and glorify and love them,

Or sages who foresee a heaven on earth.

For none of these I write, and none of these

Could read the writing if they deigned to try;

So may they flourish in their due degrees,

On our sweet earth and in their unplaced sky.

If any cares for the weak words here written,

It must be some one desolate, Fate-smitten,

Whose faith and hopes are dead, and who would die.

Yes, here and there some weary wanderer

In that same city of tremendous night,

Will understand the speech and feel a stir

Of fellowship in all-disastrous fight;

“I suffer mute and lonely, yet another

Uplifts his voice to let me know a brother

Travels the same wild paths though out of sight.”

O sad Fraternity, do I unfold

Your dolorous mysteries shrouded from of yore?

Nay, be assured; no secret can be told

To any who divined it not before:

None uninitiate by many a presage

Will comprehend the language of the message,

Although proclaimed aloud for evermore.

There is some note of a mystery lore here: an Area Lore for the city perhaps? Characters who want to destroy the city may find a certain satisfaction in learning its Lore, and sealing its mysteries.

Chapter one lays out the mood and nature of the city. The city is only manifest by night, but characters who visit it do not regain Fatigue. The city is a lot like London, but might be anywhere. Its streetlamps beam, but the houses are rarely lit. The houses have people in them, perhaps, asleep or dead, but they may have fled. If they are there, asleep, is it wrong to wake them, or is it better to put others to sleep? Note that the Vine of Death may be taken, literally, as a vis source.

I

The City is of Night; perchance of Death

But certainly of Night; for never there

Can come the lucid morning’s fragrant breath

After the dewy dawning’s cold grey air:

The moon and stars may shine with scorn or pity

The sun has never visited that city,

For it dissolveth in the daylight fair.

Dissolveth like a dream of night away;

Though present in distempered gloom of thought

And deadly weariness of heart all day.

But when a dream night after night is brought

Throughout a week, and such weeks few or many

Recur each year for several years, can any

Discern that dream from real life in aught?

For life is but a dream whose shapes return,

Some frequently, some seldom, some by night

And some by day, some night and day: we learn,

The while all change and many vanish quite,

In their recurrence with recurrent changes

A certain seeming order; where this ranges

We count things real; such is memory’s might.

A river girds the city west and south,

The main north channel of a broad lagoon,

Regurging with the salt tides from the mouth;

Waste marshes shine and glister to the moon

For leagues, then moorland black, then stony ridges;

Great piers and causeways, many noble bridges,

Connect the town and islet suburbs strewn.

Upon an easy slope it lies at large

And scarcely overlaps the long curved crest

Which swells out two leagues from the river marge.

A trackless wilderness rolls north and west,

Savannahs, savage woods, enormous mountains,

Bleak uplands, black ravines with torrent fountains;

And eastward rolls the shipless sea’s unrest.

The city is not ruinous, although

Great ruins of an unremembered past,

With others of a few short years ago

More sad, are found within its precincts vast.

The street-lamps always burn; but scarce a casement

In house or palace front from roof to basement

Doth glow or gleam athwart the mirk air cast.

The street-lamps burn amid the baleful glooms,

Amidst the soundless solitudes immense

Of ranged mansions dark and still as tombs.

The silence which benumbs or strains the sense

Fulfils with awe the soul’s despair unweeping:

Myriads of habitants are ever sleeping,

Or dead, or fled from nameless pestilence!

Yet as in some necropolis you find

Perchance one mourner to a thousand dead,

So there: worn faces that look deaf and blind

Like tragic masks of stone. With weary tread,

Each wrapt in his own doom, they wander, wander,

Or sit foredone and desolately ponder

Through sleepless hours with heavy drooping head.

Mature men chiefly, few in age or youth,

A woman rarely, now and then a child:

A child! If here the heart turns sick with ruth

To see a little one from birth defiled,

Or lame or blind, as preordained to languish

Through youthless life, think how it bleeds with anguish

To meet one erring in that homeless wild.

They often murmur to themselves, they speak

To one another seldom, for their woe

Broods maddening inwardly and scorns to wreak

Itself abroad; and if at whiles it grow

To frenzy which must rave, none heeds the clamour,

Unless there waits some victim of like glamour,

To rave in turn, who lends attentive show.

The City is of Night, but not of Sleep;

There sweet sleep is not for the weary brain;

The pitiless hours like years and ages creep,

A night seems termless hell. This dreadful strain

Of thought and consciousness which never ceases,

Or which some moments’ stupor but increases,

This, worse than woe, makes wretches there insane.

They leave all hope behind who enter there:

One certitude while sane they cannot leave,

One anodyne for torture and despair;

The certitude of Death, which no reprieve

Can put off long; and which, divinely tender,

But waits the outstretched hand to promptly render

That draught whose slumber nothing can bereave (1)

Footnote:

(1) Though the Garden of thy Life be wholly waste, the sweet flowers withered, the fruit-trees barren, over its wall hang ever the rich dark clusters of the Vine of Death, within easy reach of thy hand, which may pluck of them when it will.

In the next section the narrator follows a man, because the man seems to be walking somewhere with purpose. He discovers that the man is actually walking a ceaseless triangle between three ruins, where he lost three of his virtues. That’s not anything a player can, superficially do anything about. Arguably he can’t even kill the man because it the city the living and the dead are difficult to tell apart, although the city does seem to allow suicide. He’s very like a ghost, in Ars Magica, circling a final business monomaniacally.

The thing the player can do is destroy the triangle. Love is hard to meddle with in, but they might rekindle his failed Hope using scraps and clues in his former lodging. They might rekindle his Faith at the broken church. At minimum, they could destroy the three sites, and block the streets to them, so that he cannot make his ceaseless, pointless perambulation. They can force the cogs of the clock to stop.

II

Because he seemed to walk with an intent

I followed him; who, shadowlike and frail,

Unswervingly though slowly onward went,

Regardless, wrapt in thought as in a veil:

Thus step for step with lonely sounding feet

We travelled many a long dim silent street.

At length he paused: a black mass in the gloom,

A tower that merged into the heavy sky;

Around, the huddled stones of grave and tomb:

Some old God’s-acre now corruption’s sty:

He murmured to himself with dull despair,

Here Faith died, poisoned by this charnel air.

Then turning to the right went on once more

And travelled weary roads without suspense;

And reached at last a low wall’s open door,

Whose villa gleamed beyond the foliage dense:

He gazed, and muttered with a hard despair,

Here Love died, stabbed by its own worshipped pair.

Then turning to the right resumed his march,

And travelled street and lanes with wondrous strength,

Until on stooping through a narrow arch

We stood before a squalid house at length:

He gazed, and whispered with a cold despair,

Here Hope died, starved out in its utmost lair.

When he had spoken thus, before he stirred,

I spoke, perplexed by something in the signs

Of desolation I had seen and heard

In this drear pilgrimage to ruined shrines:

Where Faith and Love and Hope are dead indeed,

Can Life still live? By what doth it proceed?

As whom his one intense thought overpowers,

He answered coldly, Take a watch, erase

The signs and figures of the circling hours,

Detach the hands, remove the dial-face;

The works proceed until run down; although

Bereft of purpose, void of use, still go.

Then turning to the right paced on again,

And traversed squares and travelled streets whose glooms

Seemed more and more familiar to my ken;

And reached that sullen temple of the tombs;

And paused to murmur with the old despair,

Hear Faith died, poisoned by this charnel air.

I ceased to follow, for the knot of doubt

Was severed sharply with a cruel knife:

He circled thus forever tracing out

The series of the fraction left of Life;

Perpetual recurrence in the scope

Of but three terms, dead Faith, dead Love, dead Hope.

In Ars Magica, many regiones have “tempers”, which are inclinations toward emotional states or desired actions. The temper of the City, as given in the next section, is “Living death”. It tries to sap away all ability to change or hope. It sucks vitality almost like a dark faerie.

III

Although lamps burn along the silent streets,

Even when moonlight silvers empty squares

The dark holds countless lanes and close retreats;

But when the night its sphereless mantle wears

The open spaces yawn with gloom abysmal,

The sombre mansions loom immense and dismal,

The lanes are black as subterranean lairs.

And soon the eye a strange new vision learns:

The night remains for it as dark and dense,

Yet clearly in this darkness it discerns

As in the daylight with its natural sense;

Perceives a shade in shadow not obscurely,

Pursues a stir of black in blackness surely,

Sees spectres also in the gloom intense.

The ear, too, with the silence vast and deep

Becomes familiar though unreconciled;

Hears breathings as of hidden life asleep,

And muffled throbs as of pent passions wild,

Far murmurs, speech of pity or derision;

but all more dubious than the things of vision,

So that it knows not when it is beguiled.

No time abates the first despair and awe,

But wonder ceases soon; the weirdest thing

Is felt least strange beneath the lawless law

Where Death-in-Life is the eternal king;

Crushed impotent beneath this reign of terror,

Dazed with mysteries of woe and error,

The soul is too outworn for wondering.

In this next section we see that the city obeys Ars Magica’s triparate division of the self, but in a terrible way. The self is divided into the body, the soul, and the spirit. The body is the mortal part, the soul the eternal, and the spirit the part that allows the soul’s will to drive the meat, and becomes a ghost if one arises. Animals have spirits, but no souls.

Here, a prophet lost in the wilderness outside the city is saved by a dreadful vision. His soul is saved, and his body drawn away. What rest, then, for what remains of him, his haunting spirit? The player characters could perhaps lay him to rest.

IV

He stood alone within the spacious square

Declaiming from the central grassy mound,

With head uncovered and with streaming hair,

As if large multitudes were gathered round:

A stalwart shape, the gestures full of might,

The glances burning with unnatural light:—

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: All was black,

In heaven no single star, on earth no track;

A brooding hush without a stir or note,

The air so thick it clotted in my throat;

And thus for hours; then some enormous things

Swooped past with savage cries and clanking wings:

But I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Eyes of fire

Glared at me throbbing with a starved desire;

The hoarse and heavy and carnivorous breath

Was hot upon me from deep jaws of death;

Sharp claws, swift talons, fleshless fingers cold

Plucked at me from the bushes, tried to hold:

But I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Lo you, there,

That hillock burning with a brazen glare;

Those myriad dusky flames with points a-glow

Which writhed and hissed and darted to and fro;

A Sabbath of the Serpents, heaped pell-mell

For Devil’s roll-call and some fete of Hell:

Yet I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Meteors ran

And crossed their javelins on the black sky-span;

The zenith opened to a gulf of flame,

The dreadful thunderbolts jarred earth’s fixed frame;

The ground all heaved in waves of fire that surged

And weltered round me sole there unsubmerged:

Yet I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Air once more,

And I was close upon a wild sea-shore;

Enormous cliffs arose on either hand,

The deep tide thundered up a league-broad strand;

White foambelts seethed there, wan spray swept and flew;

The sky broke, moon and stars and clouds and blue:

Yet I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: On the left

The sun arose and crowned a broad crag-cleft;

There stopped and burned out black, except a rim,

A bleeding eyeless socket, red and dim;

Whereon the moon fell suddenly south-west,

And stood above the right-hand cliffs at rest:

Yet I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: From the right

A shape came slowly with a ruddy light;

A woman with a red lamp in her hand,

Bareheaded and barefooted on that strand;

O desolation moving with such grace!

O anguish with such beauty in thy face!

I fell as on my bier,

Hope travailed with such fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: I was twain,

Two selves distinct that cannot join again;

One stood apart and knew but could not stir,

And watched the other stark in swoon and her;

And she came on, and never turned aside,

Between such sun and moon and roaring tide:

And as she came more near

My soul grew mad with fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Hell is mild

And piteous matched with that accursed wild;

A large black sign was on her breast that bowed,

A broad black band ran down her snow-white shroud;

That lamp she held was her own burning heart,

Whose blood-drops trickled step by step apart:

The mystery was clear;

Mad rage had swallowed fear.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: By the sea

She knelt and bent above that senseless me;

Those lamp-drops fell upon my white brow there,

She tried to cleanse them with her tears and hair;

She murmured words of pity, love, and woe,

She heeded not the level rushing flow:

And mad with rage and fear,

I stood stonebound so near.

As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: When the tide

Swept up to her there kneeling by my side,

She clasped that corpse-like me, and they were borne

Away, and this vile me was left forlorn;

I know the whole sea cannot quench that heart,

Or cleanse that brow, or wash those two apart:

They love; their doom is drear,

Yet they nor hope nor fear;

But I, what do I here?

In this next section we see a person awaken from the regio. The key point is that it’s not an escape: this break comes only about a quarter the way through the poem. The players could use this time to find a cure: to break the regio’s tether.

V

How he arrives there none can clearly know;

Athwart the mountains and immense wild tracts,

Or flung a waif upon that vast sea-flow,

Or down the river’s boiling cataracts:

To reach it is as dying fever-stricken

To leave it, slow faint birth intense pangs quicken;

And memory swoons in both the tragic acts.

But being there one feels a citizen;

Escape seems hopeless to the heart forlorn:

Can Death-in-Life be brought to life again?

And yet release does come; there comes a morn

When he awakes from slumbering so sweetly

That all the world is changed for him completely,

And he is verily as if new-born.

He scarcely can believe the blissful change,

He weeps perchance who wept not while accurst;

Never again will he approach the range

Infected by that evil spell now burst:

Poor wretch! who once hath paced that dolent city

Shall pace it often, doomed beyond all pity,

With horror ever deepening from the first.

Though he possess sweet babes and loving wife,

A home of peace by loyal friendships cheered,

And love them more than death or happy life,

They shall avail not; he must dree his weird;

Renounce all blessings for that imprecation,

Steal forth and haunt that builded desolation,

Of woe and terrors and thick darkness reared.

VI

I sat forlornly by the river-side,

And watched the bridge-lamps glow like golden stars

Above the blackness of the swelling tide,

Down which they struck rough gold in ruddier bars;

And heard the heave and plashing of the flow

Against the wall a dozen feet below.

Large elm-trees stood along that river-walk;

And under one, a few steps from my seat,

I heard strange voices join in stranger talk,

Although I had not heard approaching feet:

These bodiless voices in my waking dream

Flowed dark words blending with sombre stream:—

And you have after all come back; come back.

I was about to follow on your track.

And you have failed: our spark of hope is black.

That I have failed is proved by my return:

The spark is quenched, nor ever more will burn,

But listen; and the story you shall learn.

I reached the portal common spirits fear,

And read the words above it, dark yet clear,

“Leave hope behind, all ye who enter here:”

And would have passed in, gratified to gain

That positive eternity of pain

Instead of this insufferable inane.

A demon warder clutched me, Not so fast;

First leave your hopes behind!—But years have passed

Since I left all behind me, to the last:

You cannot count for hope, with all your wit,

This bleak despair that drives me to the Pit:

How could I seek to enter void of it?

He snarled, What thing is this which apes a soul,

And would find entrance to our gulf of dole

Without the payment of the settled toll?

Outside the gate he showed an open chest:

Here pay their entrance fees the souls unblest;

Cast in some hope, you enter with the rest.

This is Pandora’s box; whose lid shall shut,

And Hell-gate too, when hopes have filled it; but

They are so thin that it will never glut.

I stood a few steps backwards, desolate;

And watched the spirits pass me to their fate,

And fling off hope, and enter at the gate.

When one casts off a load he springs upright,

Squares back his shoulders, breathes will all his might,

And briskly paces forward strong and light:

But these, as if they took some burden, bowed;

The whole frame sank; however strong and proud

Before, they crept in quite infirm and cowed.

And as they passed me, earnestly from each

A morsel of his hope I did beseech,

To pay my entrance; but all mocked my speech.

No one would cede a little of his store,

Though knowing that in instants three or four

He must resign the whole for evermore.

So I returned. Our destiny is fell;

For in this Limbo we must ever dwell,

Shut out alike from heaven and Earth and Hell.

The other sighed back, Yea; but if we grope

With care through all this Limbo’s dreary scope,

We yet may pick up some minute lost hope;

And sharing it between us, entrance win,

In spite of fiends so jealous for gross sin:

Let us without delay our search begin.

The odd thing in the preceding section is that the spirit the narrator is talking to already has hope. He feels they might find a grain of hope, but that feeling would, itself, suffice to allow him to pass into Hell. He’s kept in this almost-Limbo by a misunderstanding or a lie.

The box into which the spirits fling their hope is the box of Pandora, from which hope originally came. If you were to find enough hope to fill the box, the hellgate would close. Can the player characters find a spirit of hope and put it in the box?

VII

Some say that phantoms haunt those shadowy streets,

And mingle freely there with sparse mankind;

And tell of ancient woes and black defeats,

And murmur mysteries in the grave enshrined:

But others think them visions of illusion,

Or even men gone far in self-confusion;

No man there being wholly sane in mind.

And yet a man who raves, however mad,

Who bares his heart and tells of his own fall,

Reserves some inmost secret good or bad:

The phantoms have no reticence at all:

The nudity of flesh will blush though tameless

The extreme nudity of bone grins shameless,

The unsexed skeleton mocks shroud and pall.

I have seen phantoms there that were as men

And men that were as phantoms flit and roam;

Marked shapes that were not living to my ken,

Caught breathings acrid as with Dead Sea foam:

The City rests for man so weird and awful,

That his intrusion there might seem unlawful,

And phantoms there may have their proper home.

Phantoms can be destroyed with Lay To Rest the Haunting Spirit.

VIII

In this next section we see the sin of denying the spirit, which is a mortal sin.

While I still lingered on that river-walk,

And watched the tide as black as our black doom,

I heard another couple join in talk,

And saw them to the left hand in the gloom

Seated against an elm bole on the ground,

Their eyes intent upon the stream profound.

“I never knew another man on earth

But had some joy and solace in his life,

Some chance of triumph in the dreadful strife:

My doom has been unmitigated dearth.”

“We gaze upon the river, and we note

The various vessels large and small that float,

Ignoring every wrecked and sunken boat.”

“And yet I asked no splendid dower, no spoil

Of sway or fame or rank or even wealth;

But homely love with common food and health,

And nightly sleep to balance daily toil.”

“This all-too-humble soul would arrogate

Unto itself some signalising hate

From the supreme indifference of Fate!”

“Who is most wretched in this dolorous place?

I think myself; yet I would rather be

My miserable self than He, than He

Who formed such creatures to His own disgrace.

“The vilest thing must be less vile than Thou

From whom it had its being, God and Lord!

Creator of all woe and sin! abhorred

Malignant and implacable! I vow

“That not for all Thy power furled and unfurled,

For all the temples to Thy glory built,

Would I assume the ignominious guilt

Of having made such men in such a world.”

“As if a Being, God or Fiend, could reign,

At once so wicked, foolish and insane,

As to produce men when He might refrain!

“The world rolls round for ever like a mill;

It grinds out death and life and good and ill;

It has no purpose, heart or mind or will.

“While air of Space and Time’s full river flow

The mill must blindly whirl unresting so:

It may be wearing out, but who can know?

“Man might know one thing were his sight less dim;

That it whirls not to suit his petty whim,

That it is quite indifferent to him.

“Nay, does it treat him harshly as he saith?

It grinds him some slow years of bitter breath,

Then grinds him back into eternal death.”

IX

There are ships in the river, and drays in the streets. There must be manufacturing of something occurring here. The player characters could trace and destroy that industry.

It is full strange to him who hears and feels,

When wandering there in some deserted street,

The booming and the jar of ponderous wheels,

The trampling clash of heavy ironshod feet:

Who in this Venice of the Black Sea rideth?

Who in this city of the stars abideth

To buy or sell as those in daylight sweet?

The rolling thunder seems to fill the sky

As it comes on; the horses snort and strain,

The harness jingles, as it passes by;

The hugeness of an overburthened wain:

A man sits nodding on the shaft or trudges

Three parts asleep beside his fellow-drudges:

And so it rolls into the night again.

What merchandise? whence, whither, and for whom?

Perchance it is a Fate-appointed hearse,

Bearing away to some mysterious tomb

Or Limbo of the scornful universe

The joy, the peace, the life-hope, the abortions

Of all things good which should have been our portions,

But have been strangled by that City’s curse.

X

Here, the City perverts the True Love Virtue, which so often defies the Infernal, by twisting it into idolatry. The players can end it by breaking the tableau somehow.

The mansion stood apart in its own ground;

In front thereof a fragrant garden-lawn,

High trees about it, and the whole walled round:

The massy iron gates were both withdrawn;

And every window of its front shed light,

Portentous in that City of the Night.

But though thus lighted it was deadly still

As all the countless bulks of solid gloom;

Perchance a congregation to fulfil

Solemnities of silence in this doom,

Mysterious rites of dolour and despair

Permitting not a breath or chant of prayer?

Broad steps ascended to a terrace broad

Whereon lay still light from the open door;

The hall was noble, and its aspect awed,

Hung round with heavy black from dome to floor;

And ample stairways rose to left and right

Whose balustrades were also draped with night.

I paced from room to room, from hall to hall,

Nor any life throughout the maze discerned;

But each was hung with its funereal pall,

And held a shrine, around which tapers burned,

With picture or with statue or with bust,

all copied from the same fair form of dust:

A woman very young and very fair;

Beloved by bounteous life and joy and youth,

And loving these sweet lovers, so that care

And age and death seemed not for her in sooth:

Alike as stars, all beautiful and bright,

these shapes lit up that mausolean night.

At length I heard a murmur as of lips,

And reached an open oratory hung

With heaviest blackness of the whole eclipse;

Beneath the dome a fuming censer swung;

And one lay there upon a low white bed,

With tapers burning at the foot and head:

The Lady of the images, supine,

Deathstill, lifesweet, with folded palms she lay:

And kneeling there as at a sacred shrine

A young man wan and worn who seemed to pray:

A crucifix of dim and ghostly white

Surmounted the large altar left in night:—

The chambers of the mansion of my heart,

In every one whereof thine image dwells,

Are black with grief eternal for thy sake.

The inmost oratory of my soul,

Wherein thou ever dwellest quick or dead,

Is black with grief eternal for thy sake.

I kneel beside thee and I clasp the cross,

With eyes forever fixed upon that face,

So beautiful and dreadful in its calm.

I kneel here patient as thou liest there;

As patient as a statue carved in stone,

Of adoration and eternal grief.

While thou dost not awake I cannot move;

And something tells me thou wilt never wake,

And I alive feel turning into stone.

Most beautiful were Death to end my grief,

Most hateful to destroy the sight of thee,

Dear vision better than all death or life.

But I renounce all choice of life or death,

For either shall be ever at thy side,

And thus in bliss or woe be ever well.—

He murmured thus and thus in monotone,

Intent upon that uncorrupted face,

Entranced except his moving lips alone:

I glided with hushed footsteps from the place.

This was the festival that filled with light

That palace in the City of the Night.

This is fantastic! I have been working on a post about Melencholia I for my teaching blog, since there’s a lot of math in there. But the poem is an amazing source as well, and I will need to read it a few more times. Thanks for sharing this!

LikeLiked by 1 person